On this blog, I write about some of the most important aspects of Christian spirituality in early medieval England. The feast of Easter. The healing of the sick. Confession. Expressing one’s deepest yearnings to God in prayer.

And now: cheese.

I’ve written before about Ælfric of Eynsham, abbot and homilist, and also the author of a surprisingly (since it’s Ælfric) sweet little text known as the Colloquy on the Occupations. Apparently designed for young monks who were learning Latin, it takes the form of a dialogue between a novice monk and people in various rural occupations, whom he interviews about their jobs. One of these is the shepherd, who tells the monk that he must protect his sheep, and milk them twice daily, telling him, ‘I make butter and cheese’. So one of the first things that students of Latin learned was how to talk about dairy products. They had their priorities right.

What is more, an Old English version of this text survives, so, for those of us who read Mitchell and Robinson’s A Guide to Old English, it is also one of the first things that we learned how to read in Anglo-Saxon: ‘ic macie buteran and ciese’.

Unfortunately, we are not told exactly what kind of cheese the shepherd is making. Soft or hard, mild or mature? And which goat’s and cow’s cheeses were around in Anglo-Saxon England? Perhaps they made something like this Viking cheese, gamalost. In her research into Anglo-Saxon food, Ann Hagen argues that even new cheeses appear to have been relatively firm, and would have been more easily available to the poor than mature cheeses, which required the time and cost of ripening; there is no hard evidence for the presence of blue (fynig, i.e. mouldy) cheese in the Anglo-Saxon period.

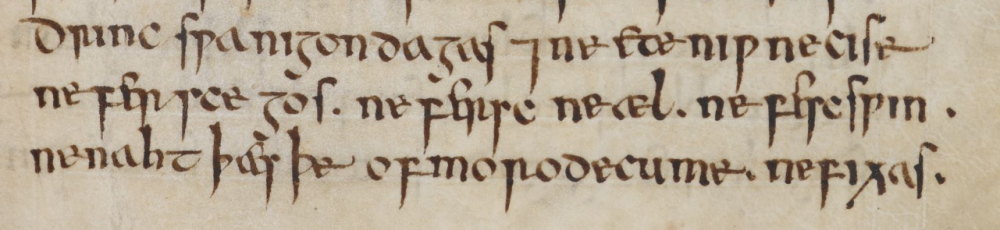

Of course, you can easily have too much of a good thing. Sufferers from circul adl (translated by Oswald Cockayne as ‘shingles’) are advised to take a medicine and abstain from certain foods:

Drink thus for nine days and do not eat new cheese, nor fresh goose, nor fresh eel, nor fresh pig, nor anything that comes in spiced wine …

But in other circumstances, cheese could have positive, indeed medicinal, uses. According to the Leechbook (fol. 47v), eating new cheese and wheat bread was a recommended treatment for those suffering from smega wyrm, a penetrating worm, and cheese and honey for dysentery (fols. 106v-107r). It’s also recommended for a witseoc person (fol. 120v) – presumably someone suffering from a form of mental disturbance:

If you want to heal a wit-sick person, get a container full of cold water. Drip it three times on the drink, bathe the person in the water, and let the person eat blessed bread and cheese and garlic and cropleek, and drink a cupful of the drink …

The adjective g(e)halgodne (blessed) refers grammatically to the bread – were the cheese and garlic blessed too? Blessed cheese is certainly not alien to the Christian tradition. The Apostolic Tradition, a third-century book of liturgical traditions attributed to the martyr Hippolytus, and possibly recording a time already gone by, includes a blessing for cheese and olives. Although the Greek original is now lost, this part of the treatise survives in Latin translation:

Similiter si quis caseum et olivas offeret, ita dicet: Sanctifica lac hoc quod quoagulatum est, et nos conquaglans tuae caritati …

Likewise if any one offers cheese and olives he shall say thus: Sanctify this solidified milk, solidifying us also unto Thy charity …

Ed.and trans. Gregory Dix, The Apostolic Tradition, p. 10.

In other words, cheese can bring you closer to God. Is it any wonder?

(And, while we’re on the subject, ‘quoagulare’, as it is spelled here, and ‘conquaglare’ are now my favourite Latin words of all time.)

If we return to eleventh-century England, we will find blessings of cheese still being written down, such as in a collection of blessings for Easter in the tenth-century manuscript known as the Egbert Pontifical:

Blessing of cheese and of butters, and all foods. God, who made and created the sustenance of your generosity for all living things, and incessantly refresh humankind by the dishes and cups of your precepts and by the earthly substances of your gifts, we ask you resolutely, Jesus almighty, that you yourself, who created and gave us this creature [name] of the form either of cheese or of butter, or whatever it may be, may deign to sanctify and bless these your gifts, by your everlasting and illustrious favour, and to those feeding from them set the bountiful health of your blessing gently in their stomachs, and mercifully grant them the safety of this present life and the blessing of the yet to come.

Imagine that. Holy cheese!

But cheese also had a more sinister use. Some early medieval liturgical books contain an ordeal using barley bread and cheese – a way of ascertaining a person’s guilt or innocence via the eating of small pieces of food. It operates upon the same rationale as ducking witches – nature rejects someone who has done wrong, so a guilty person will choke on the bread or cheese. Sarah Larratt Keefer has written on this corsnæd ordeal, noting that early medieval barley bread and cheese may well have been difficult to chew and have contained toxins that would encourage the eater to retch.

In earlier posts, I have mentioned the Portiforium of St Wulfstan (Cambridge, Corpus Christi College MS 391), a compendium of liturgical and other useful texts which originally belonged to St Wulfstan, Bishop of Worcester, and was written at around the time of the Norman Conquest. On pp. 571-3 of this manuscript there appears one such rite, with these instructions:

Primitus faciat sacerdos ut supra diximus cum letania et omnes qui cum eo sunt ieiuni persistant donec consecratio panis et casei perficiatur et simul in os punatur [sic] et simul comedatur et si est culpabilis euomat illud, ut in omnibus honorificetur deus.

Hughes, ed., Portiforium of St Wulstan, I, 169.

First of all, let the priest do as we said above, with the litany, and may all the people who are with him continue fasting until the consecration of bread and cheese is completed, and let it be placed in the mouth at the same time and eaten at the same time, and if he is guilty, may he vomit it out, so that in all things God may be honoured.

The subsequent prayer asks that God may send his spirit upon this bread and cheese, and constrict the person’s/people’s inner organs, so that his/their throat(s) may close up and prevent him/them from consuming the bread or cheese. This process is useful for ascertaining guilt in cases of theft, or even murder. Another such ordeal can be found in the Red Book of Darley (Cambridge, Corpus Christi College MS 422), on pages 339-44. You could write a medieval murder mystery where the identity of the murderer is (supposedly) found out by seeing who chokes on the cheese.

But I won’t be choking on mine. As Monty Python once said – blessed are the cheesemakers!

Works used:

M. J. Banting, ed., Two Anglo-Saxon Pontificals (The Egbert and Sidney Sussex Pontificals), Henry Bradshaw Society 104 (London: Boydell Press, 1989).

Oswald Cockayne, ed., Leechdoms, Wortcunning, and Starcraft of Early England, Rolls Series 35:1-3 (New York: Kraus Reprint, 1965).

Gregory Dix, ed., The Treatise on the Apostolic Tradition of St Hippolytus of Rome, Bishop and Martyr (London: SPCK, 1937), repr. with corrections by Henry Chadwick (London: SPCK, 1968).

Ann Hagen, A Handbook of Anglo-Saxon Food: Processing and Consumption, 2nd rev. (Chippenham: Anglo-Saxon Books, 1998).

Anselm Hughes, ed., The Portiforium of Saint Wulstan (Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, MS. 391), 2 vols., HBS 89-90 (Leighton Buzzard: Faith Press, 1958-60).

Sarah Larratt Keefer, ‘Ut in omnibus honorificetur Deus: The Corsnæd Ordeal in Anglo-Saxon England’, in Joyce Hill and Mary Swan, eds., The Community, the Family and the Saint: Patterns of Power in Early Medieval Europe (Turnhout: Brepols, 1998), 237-64.

Fascinating stuff. ” You could write a medieval murder mystery where the identity of the murderer is (supposedly) found out by seeing who chokes on the cheese” <—— please do this!

LikeLike