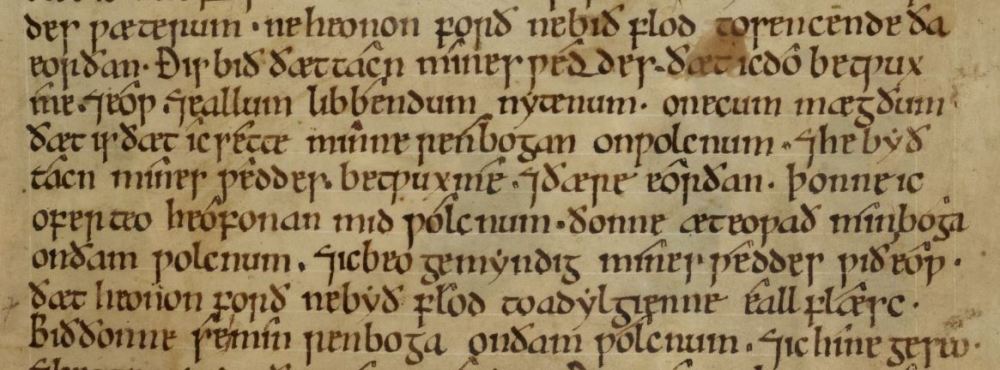

This is the sign of my covenant, that I make between me and you and all living creatures for all generations, that is that I will set my rainbow in the clouds and it will be a sign of my covenant between me and the earth: when I cover the heavens with the clouds, then my rainbow will appear in the clouds and I will be mindful of my covenant with you that henceforth there will not be a flood to destroy all flesh.

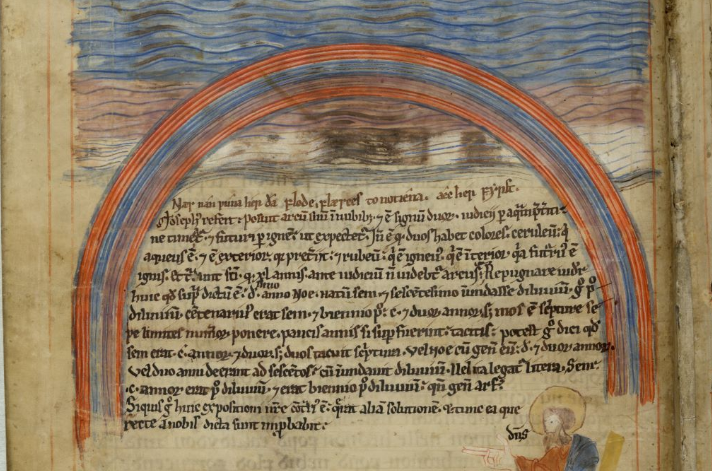

In Genesis 9:8-17, God creates the rainbow as a sign to Noah that he would never flood the earth again. These are the words of the Old English Hexateuch, an eleventh-century illustrated copy of the early books of the Bible translated into Old English prose. Overleaf, the artist depicts the first rainbow thus:

Here, the many colours of the rainbow are represented by stripes in just three colours. Why is this? Isidore’s encyclopaedic work De natura rerum asserts that there are, in fact, four colours in the rainbow, and gives a reason why:

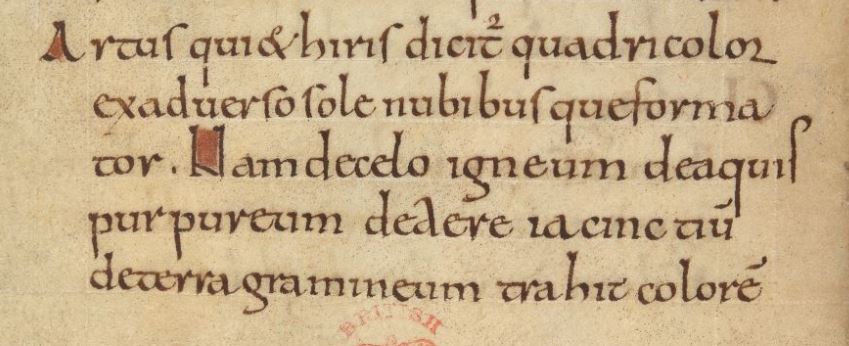

Quadricolor enim est . ex omnibus elementis in se rapit species. De celo enim trahit igneum colorem . de aquis purpureum . de aere album de terris collegit nigrum.

For it is of four colours, and takes its appearance from all of the elements into itself. From the sky it draws the fiery colour, from the waters purple, from the air white, and from the earth it gathers black.

In earlier posts, I have discussed the manuscript known as Ælfwine’s Prayerbook (London, British Library Cotton Titus D. xxvii+xxvi), a little eleventh-century handbook which once belonged to Ælfwine, the dean of the New Minster in Winchester. The dean was evidently keen on scientific knowledge and how to foretell the future, as a significant portion of the manuscript is made up of little scraps of knowledge about the tides and changing seasons, and prognostics for different activities (such as bloodletting). On fols. 5v-6r of Titus D. xxvi there appears a random little snippet about the rainbow, along much the same lines as the one in De natura rerum:

The rainbow, which is also called ‘iris’, is of four colours and is formed from the opposition of the sun and the clouds, for it draws its fiery colour from the sky, purple from the waters, blue from the air, and green from the earth, and it is not separated, except in a full moon.

The two manuscripts disagree on the colours drawn from the air – are they white and black, or blue and green? I’d hate to think what medieval writers would have made of The Dress. Since the nineteenth century, there has been an interesting discussion, summarised by the linguist Guy Deutscher in his excellent book Through the Language Glass: How Words Colour Your World, about what the colour words in ancient writings tell us about how people in different eras of history perceived colours: the works of Homer, for instance, refer to few colours, and how the ancient Greeks categorised them seems to be drastically different from the thought patterns with which we are familiar. A similar phenomenon can be seen in the Old English poem Beowulf: as Jennifer Neville notes,

Colour-words are not self-evident: while Modern English focuses almost exclusively on hue, other languages may emphasize tone, saturation, or surface effects instead … Old English was not at the same stage of development as Modern English in its vocabulary for colour.

Neville, ‘Hrothgar’s Horses’, p. 146

Isidore’s theory draws on the belief in the four basic elements that make up the world, an idea which is explained in De temporibus anni, an Old English treatise on science based on the Latin works of the eighth-century St Bede, of which one copy can be found in Ælfwine’s Prayerbook itself.

Þeos lyft þe we on lybbað is an ðæra feower gesceafta · þe ælc lichamlic ðing on wunað;

Feower gesceafta sind · þe ealle eorðlice lichaman on wuniað · þæt sind · Aer · Ignis · Terra · Aqua;

Aer · is lyft · Ignis · fyr · Terra · eorðe · Aqua · wæter.

Henel, ed., De Temporibus Anni, p. 72.

This air in which we live is one of the four created things in which every physical thing exists. The four created things in which all earthly things exist are aer, ignis, terra and aqua. Aer is air, ignis is fire, terra is earth, and aqua is water.

These four elements mixed together constitute the whole of the physical world: if I’ve understood correctly, according to the text in the prayerbook, the opposition of the sun and the clouds causes them to split and become visible to us in some manner. The reason why the author saw four colours in the rainbow comes from the theory of the four elements, an idea which goes back to Aristotle. But why those particular colours?

In the seventeenth century, Isaac Newton demonstrated that white light was made up of all the colours of the rainbow by passing it through a prism. But he too faced the question of how many colours those were. For Newton, that number had to be seven, the same as the notes in a musical scale – so, once more, the number of colours was decided by a theory about the world that has nothing to do with light – and he included the colours orange and indigo to allow for this. Even now, people tend to think of the rainbow in terms of seven colours: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet.

So how many colours are there really? In this blogpost, Ethan Siegel explains that

going off of unique frequencies, there are more colors in a rainbow than there are stars in the Universe or atoms in your body, but that goes far beyond what we can perceive. Your imperfect eye can (probably) only discern about a million distinct colors when you view a rainbow, or anything else, for that matter.

Far more than Aristotle, Isidore, Bede, or Newton would have expected! It seems that there are as many colours in the rainbow as we are prepared to see.

Works used:

Heinrich Henel, ed., Aelfric’s De Temporibus Anni, EETS 213 (London: OUP, 1942).

Jennifer Neville, ‘Hrothgar’s Horses: Feral or Thoroughbred?’, Anglo-Saxon England 35 (2006): 131-57.

I’m wondering if sometimes the accepted colors of the rainbow influenced the number of colors of ink one aimed for in a manuscript. I know, that’s a secondary concern to the kinds of ink available. But it makes sense when there are limited colors available, we tend to want each of them to symbolize something.

LikeLike

Ooh, interesting thought, thanks!

LikeLike

What did English speakers call the colour orange before oranges were available in English-speaking countries?

LikeLike

Off the top of my head, I believe it fell under the heading of “red” (think of redheads, robin redbreasts, both just orange) – I must look up a good source for that though!

LikeLike

Different shades of orange are just as well described as shades of red or yellow depending on their hue. When does a reddish-orange become just an orangey-red? When does a yellow become an orange?

LikeLike

I find it interesting that the color in between blue and green (cyan/teal) is just as distinctive on the color wheel as orange, but that color doesn’t find a place in a box of 10 crayons, so it’s not part of many people’s simple color vocabulary. Many people end up calling it “blue”, which helps me understand a time when “orange” wasn’t part of normal color vocabulary and people would instead call that color “red”.

LikeLike

In Sweden it was called “Brandgul” (firey yellow). – Why mention that?

Vikings impacted the english language alot so I didn’t find it a way to long reach to asume there could be a bridge here further back.

LikeLike

IIRC, it was ‘red yellow’ or ‘yellow red’.

LikeLike

The people of the earth saw the same rainbows we see today, so the ones on these texts are symbolic. It would be interesting to see where other rainbows are portrayed, possibly in churches of that era. Thank you for your research! I always enjoy your posts.

LikeLike

I won’t be able to find it quickly but id memory serves the Eddas refer to three colours in the rainbow.

LikeLike

Oooh, thanks for that! I must look it up.

LikeLike

This was such an interesting post! I had never thought about the significance of the colours, thanks for sharing!

LikeLike

Another really interesting post that started me wondering when it was settled on 7 colours (and when Descartes gave his classic explanation, how many did he see?!)

LikeLike