I recently wrote a blogpost about fruit in Anglo-Saxon England, including the fruit in the Garden of Eden, and that got me thinking: whose idea was it to eat the fruit in the first place? Snakes are abundant in medieval manuscripts if you know where to look – tempting Eve, biting people, generally causing a nuisance – and so are solutions to the problems which they caused.

So let’s return to the Edenic snake first of all:

Et serpens erat callidior cunctis animantibus agri, quae fecerat Dominus Deus. Qui dixit ad mulierem: “Verene praecepit vobis Deus, ut non comederetis de omni ligno paradisi?”.

Cui respondit mulier: “De fructu lignorum, quae sunt in paradiso, vescimur;

de fructu vero ligni, quod est in medio paradisi, praecepit nobis Deus, ne comederemus et ne tangeremus illud, ne moriamur”.

Dixit autem serpens ad mulierem: “Nequaquam morte moriemini!

Scit enim Deus quod in quocumque die comederitis ex eo, aperientur oculi vestri, et eritis sicut Deus scientes bonum et malum”.

Now the serpent was more subtle than any of the beasts of the earth which the Lord God made. And he said to the woman: Why hath God commanded you, that you should not eat of every tree of paradise?

And the woman answered him, saying: Of the fruit of the trees that are in paradise we do eat:

But of the fruit of the tree which is in the midst of paradise, God hath commanded us that we should not eat; and that we should not touch it, lest perhaps we die.

And the serpent said to the woman: No, you shall not die the death.

For God doth know that in what day soever you shall eat thereof, your eyes shall be opened: and you shall be as Gods, knowing good and evil.

Genesis 3:1-5, Vulgate and Douay-Rheims, Unbound Bible

St Ephrem the Syrian (d. 373), whom we have met before in this blog, apparently once theorised that, if Adam and Eve had just cooled it and waited a while, God would have let them have the knowledge of good and evil later on. For the snake, knowledge isn’t something to work patiently for, but something that can be achieved instantly. (Let this story serve as a warning to politicians who want to put a price tag on education.) However, the eighth-century Northumbrian monk and scholar St Bede, in his commentary on Genesis, rather more conventionally insists that the snake was possessed by the spirit of the devil:

This serpent can be said to be ‘more subtle than any of the beasts’ not by reason of its own irrational mind, but from a spirit up to then foreign to it, that is, a diabolic spirit.

Bede, On Genesis, trans. Calvin Kendall, p. 125.

The illustrator of the Old English Genesis poem apparently thought the same way: in that manuscript, the tempter is portrayed not as a snake, but as an angel with a tail.

In the accompanying poem, however, Eve insists that her tempter was strictly serpentine (the Old English word for snake, næd(d)re, would later become the modern ‘adder’):

Me nædre beswac and me neodlice

to forsceape scyhte and to scyldfrece,

fah wyrm þurh fægir word.

Genesis, ll. 857-9. www.oepoetry.ca

A snake deceived me, and eagerly incited me to a terrible act and to sinful greed, a brightly coloured [or hostile] worm, through fair words.

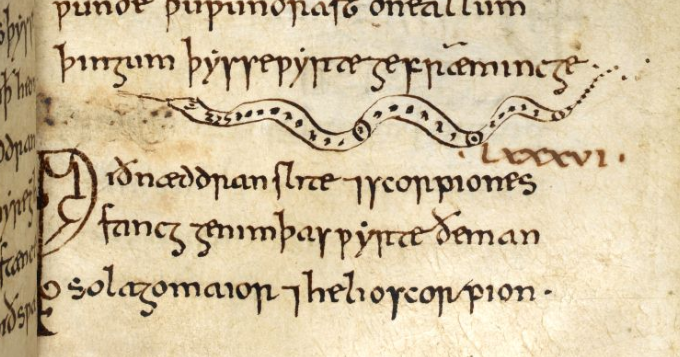

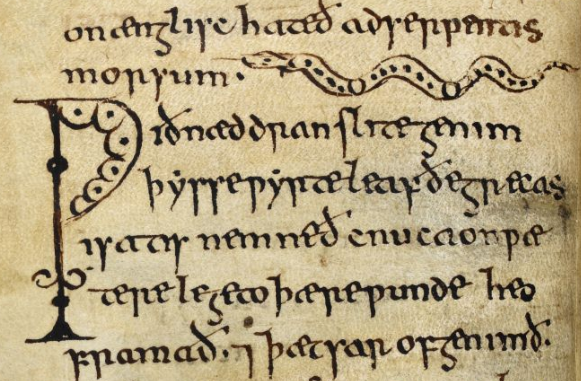

So a snake started off all of humanity’s problems; and since then they haven’t got any easier to deal with, what with their unfortunate tendency to bite people. But for the compilers of the medieval Herbarium, any number of remedies for serpent strikes could be found amongst the plants and flowers. I have discussed this medical compendium in a number of earlier blogposts, and, in particular, the copy in the late tenth-/early eleventh-century manuscript London, British Library Harley MS 585. Throughout the manuscript, there are a number of cures for snakebite, many of which have little snakes drawn beside them:

Against snake’s bite and scorpion’s sting, take this plant which one [calls] solago maior and helioscorpion.

Against snake’s bite, take the leaves of this plant which the Greeks call isatis, pound [it] in water, lay it onto the wound; it will work, and the pain will go away.

isatis will sort that out. Cambridge, Trinity College O.2.48, fol. 136r. ?Germany, 14th century.

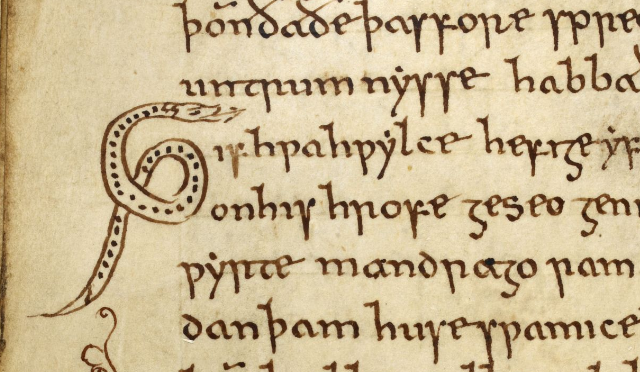

Now, Harley 585 is a pretty plain manuscript. Its concession to ornament is mostly limited to a fondness for fancy letter wynns. So it is all the more strange, then, that it is seething with marginal illustrations of snakes. Usually these appear when a snake is mentioned in the text, but sometimes they are simply found hiding in the vellumy undergrowth, lying in wait for you, cunningly disguised as the letter G.

I’ve found no fewer than fourteen snakes basking in the Harley 585 copy of the text (plus a dragonish sort of thing) – if you take a look through, you can find them all here.

But let’s slither further afield. The Old English prose text Wonders of the East has some useful advice for anyone who wishes to harvest pepper in the lands between Babylon and ‘the city of Persia’:

In those lands there is an abundance of pepper; the snakes hold that pepper in their desire. One takes the pepper thus, so that one sets fire to the place, and then the snakes [come] down onto the earth, so that they flee, because the pepper is black.

The author of The Wonders of the East is mostly just interested in describing what is to be found in faraway lands, but the text known as Physiologus talks about animals in order to teach lessons about human behaviour and living the Christian life. A Middle English version of this in London, British Library MS Arundel 292, written in around 1300 and perhaps in Norwich, tells us how the snake sheds its skin (by squeezing through a stone with a hole in it) and that it is peculiarly selective about whom it attacks:

If he naked man se, ne wile he him no3t (n)e33en,

Oc he fleð fro him, als he fro fir sulde.

If he cloðed man se, cof he waxeð,

For up he ri3teð him, redi to deren.

Hanneke Wirtjes, ed., The Middle English Physiologus, p. 6.

(If he see a naked man, he will not challenge him, but he will flee from him, as he would from fire. If he see a clothed man, he grows bold, for he rears himself up, ready to harm.)

This, as the c. 1200 Aberdeen Bestiary (Aberdeen University Library, Univ Lib. MS 24) explains, is because Adam was naked in Paradise, when he was still perfect and unfallen.

Sic et nos spiritualiter intelligamus quia primus homo Adam quamdiu fuit nudus in Paradiso non prevaluit serpens exilire in eum, sed postquam est indutus, id est mortalitate corporis, tunc exilivit in eum serpens.

In the same way, we are to understand in spiritual terms, that for as long as Adam, the first man, was naked in Paradise, the serpent was unable to attack him; but after he was clothed, that is, in mortal flesh, then the serpent assaulted him.

Text and translation from Aberdeen Bestiary project, fol. 71r.

So there we have it: Adam was safe from snake attacks all along – the solution was being naked.

Thanks to Hollie Morgan and Vicki Blud for the discussion of snaky syntax in Middle English.

Works cited:

Calvin B. Kendall, trans. Bede, On Genesis, Translated with an Introduction and Notes (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2008).

Hanneke Wirtjes, ed., The Middle English Physiologus, EETS 299 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991).

For St Ephrem:

Sebastian Brock, trans., The Syriac Fathers on Prayer and the Spiritual Life (Kalamazoo, Michigan: Cistercian Publications, 1987), p. xxiii.

Awesome. I love the Harley snakes! Of course, Bede, in his ecclesiastical history, tells us that all we need is something from Ireland:

“No reptiles are found there [i.e. Ireland], and no snake can live there; for, though often carried thither out of Britain, as soon as the ship comes near the shore, and the scent of the air reaches them, they die. On the contrary, almost all things in the island are good against poison. In short, we have known that when some persons have been bitten by serpents, the scrapings of leaves of books that were brought out of Ireland, being put into water, and given them to drink, have immediately expelled the spreading poison, and assuaged the swelling.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good one! One thing I was originally going to write about, but decided against on grounds of length/time, was the remedies in the “Lacnunga” section of Harley 585, which use corrupted Irish words as a cure for various things, including, I think, poison and snakebite. There is certainly something called the “wyrmgealdor” – snake/worm incantation.

LikeLiked by 1 person