So you’re scrolling through your Facebook feed, and one of those memes pops up. You know what I mean. Either it’s a sick child who needs your prayers (‘1 like = 100 prayers!’), or a cursed photo of a hellwraith (‘like and share or you’ll die tonight!!’), or simply an inspirational image which will give you a whole day’s good luck if you repost it, an image which has become completely detached from its original purpose. The one below is probably the most baffling example that I have come across so far.

Medieval prayers could be a little bit like that sometimes. Some were considered to be particularly effective, so monks and nuns recopied them again and again. In my research, I have had to get my head around a complex web of prayers, tracing the connections between one manuscript and many others. And sometimes a little piece of text would be written above a prayer, promising blessings in this world and/or the next if you said it. Just as in the memes of today, prayers and their rubrics sometimes became detached from one another, and reattached to other rubrics/prayers, as they were copied and passed on.

In an earlier post, I discussed a small set of prayers for use in the early morning in the manuscript known as Ælfwine’s Prayerbook. At the end of the text, the writer explains why it is important to sing the daily liturgy of the hours:

Gyf þu ælce dæge þine tidsangas wel asingst, ne þearft ðu næfre to helle, 7 eac on þisse worulde þu hæfst þe gedefe lif. 7 gyf ðu on hwilcum earfeðum byst 7 to Gode clypast, he ðe miltsað 7 eac tiþað, þonne þu hine bitsð. Amen.

(Quoted from Günzel, ed., Ælfwine’s Prayerbook, p. 143.)

(If you sing your Hours well every day, you need never go to hell, and in this world too you will have a good life. And if you are in any kind of trouble and call to God, he will have mercy on you and also give to you, when you ask him. Amen.)

More commonly, though, this sort of promise precedes the text of a specific prayer, which was believed to be particularly good for protective purposes. A confessional prayer in the mid-eleventh century Bury Psalter begins with this extravagant promise:

Incipit inquisitio Sancti Augustini. De ista oratione in quacumque die cantauerit aliquis istam orationem non nocebit illi diabolus neque ullus homo inpedimentum facere potest. Et quod iustus petierit a Deo dabitur ei. Et si anima sua egrediatur de corpore in infernum non exiet.

Vatican City, Bibliotheca apostolica vaticana Reg. lat. 12, fols. 165v-166r

(Here begins the inquiry of St Augustine. Regarding this prayer: on whatever day someone has sung this prayer, a devil will not harm him, nor can another man do him hindrance. And what a just man asks from God will be given to him. And if his spirit goes out of his body, it will not go into Hell.)

A shorter version of this rubric appears above the same prayer in a couple of other manuscripts; and there is something similar in Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 391, but there it is attached to an altogether different prayer, attributed to St Gregory, not St Augustine (rather like the inspirational quotes on Facebook, prayers in medieval manuscripts could be credited either to the actual author or somebody different altogether).

What I find interesting about these rubrics is that a particular prayer is said to have specific effects, often things which have little to do with the actual content of the prayer: they could just as easily be attached to another. What’s more, the rubrics promise both physical and spiritual help (protection from bad people and from devils), help both on earth and after death (a good life in this world, and never needing to go to hell).

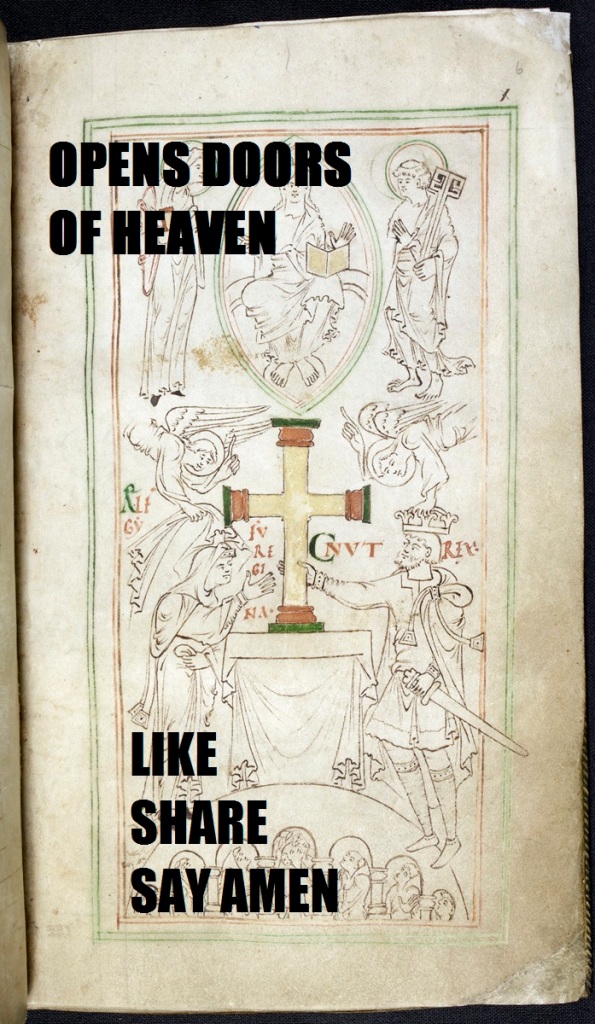

And what about the more negative, threatening memes (‘Share this image or you’ll die tonight!’)? I recently visited the British Library to take a look at Ælfwine’s Prayerbook, and also at another manuscript called Cotton Tiberius A. iii. Each of these contains some groups of prayers to the Holy Cross, and there is a noticeable amount of overlap between the two manuscripts. (Ælfwine’s Prayerbook dates from the second quarter of the eleventh century, and was written in Winchester; Tiberius A. iii is mid-eleventh century and was probably written at Christ Church, Canterbury). Amongst these sets of prayers sits a list of reasons why it is important to venerate the cross:

HAE SVNT .IIII. CAVSAE QVIBUS SANCTA CRUX ADORATVR.

PRIMA CAVSA EST, QVI IN VNA DIE septem cruces adit, aut septies unam crucem adorat, septem porte inferni clauduntur illi, et septem porte paradisi aperiuntur ei.

Secunda causa est, si primum opus tuum tibi sit ad crucem, omnes demones, si fuissent circa te, non potuissent nocere tibi.

Tertia causa est, qui non declinat ad crucem, non recipit pro se passionem Christi, qui autem declinat, recepit eam et liberabitur.

Quarta causa est, quantum terrae pergis ad crucem, quasi tantum de hereditate propria offeras Domino.

(Quoted from Gunzel, Aelfwine’s Prayerbook, p. 126.)

(These are four reasons why the holy cross is adored.

The first reason is, whoever approaches seven crosses in one day, or adores one cross seven times, seven doors of hell are closed to him, and seven doors of paradise are opened to him.

The second reason is, if your first act for yourself is to the cross, all the demons, if they have been around you, would not have been able to harm you.

The third reason is, whoever does not bow to the cross does not receive the passion of Christ for himself; but whoever does bow has accepted it and will be saved.

The fourth reason is, as much land as you walk on when approaching the cross will be as much as your own inheritance which you offer to the Lord.)

These are mostly positive: if you venerate the cross, God will give you good things. Only the third warns the reader of what will happen if they do not do so. The advice is not so far removed from the ‘like and repost’ memes of today.

It would be interesting to know how Anglo-Saxon monks and nuns understood these prayers to work: unfortunately, none are now available for comment. Were the words themselves so holy that they brought about the blessings automatically, so to speak; or was prayer somewhat more personal than that? Hopefully, I’ll write another blogpost soon about how medieval people envisaged their prayers as hitting God’s ears.

Very interesting and inspiring. Informative blog, love it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting. Very like the way prayers are used as medicine in North Africa, including as slips of paper burned and wrapped in a bag with other magical items.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That sounds really interesting, thanks!

LikeLike

This was interesting to say the least. Great blog very informative, kept me hooked right until the end.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a fun way to see today and yesterday. I appreciate your angle, very much so–

LikeLiked by 1 person

If you like books and poems etc please check out my blog

fluffypuffyrainbow.wordpress.com

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love this post. The comparison to modern “share this if…” memes is both apt and hilarious.

LikeLiked by 1 person

PATER noster, qui es in caelis, sanctificetur nomen tuum. Adveniat regnum tuum. Fiat voluntas tua, sicut in caelo et in terra. Panem nostrum quotidianum da nobis hodie, et dimitte nobis debita nostra sicut et nos dimittimus debitoribus nostris. Et ne nos inducas in tentationem, sed libera nos a malo. Amen.

LikeLiked by 1 person